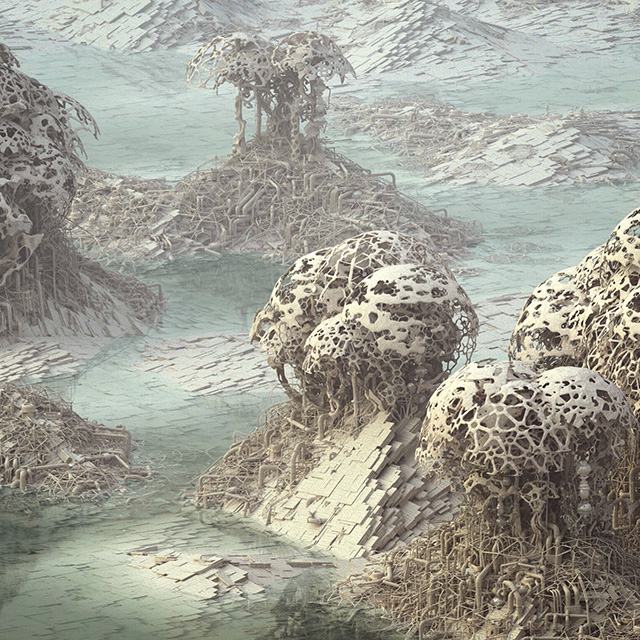

Here's a couple of recent instagrams I posted. These are details of much larger renders which I'm not quite ready to reveal (until my show in October, at the Red Head Gallery in Toronto).

I plan to print some of them roughly 8 feet x 4 feet, at a crisp 300 dots per inch. This requires coaxing out renders 28,800 pixels wide. I'm constantly bumping into hardware and software limitations. Thankfully I can farm out these huge renders, as my machine alone would take well over a week to get through one.

The process of making these involves a great variety of stages and components, which range from drawing and virtual sculpture to something more akin to programming. I start with a set of elements numbering roughly 300 at last count, which include things like rocks, trees, buildings, abstract forms, etc.. These are then randomly scattered in vast numbers across a given terrain (itself possibly randomly generated).

Each set of randomized elements must follow a set of rules of my choosing. For example, I might say "rocks, you are only allowed to exist at altitudes between 15 and 23.7 meters", or "trees you may only grow on slopes of between 30 and 45 degrees", and so on. The system remains live, and I can change a single parameter and the random arrangement will shuffle itself into a new configuration based on the tweaked rules. I can view previews of the state of the system at any time. For every proper render I do, I flit past several variations that will never be seen again. After enough noodling I'll get to something I like, save the settings and do a medium-sized render (as in maybe 9000 pixels wide) which my computer can render overnight. Based on those renders I will opt to refine some of them further into much larger images. Along the way, the scenes acquire ever more computer-straining bulk, which makes the going quite slow.

On its own, any given procedural system based on a simple set of rules will tend to look obviously artificial. When combined with several others you start to get a rough approximation of something natural. If you look closely you will notice that the whole image consists of the same objects repeated in different configurations.

Working with randomness in this way leads to compositions that I would likely never contrive when drawing. Its more like photographing a landscape - an ever-shifting landscape that exists as a collaboration between myself and randomly emergent patterns - a landscape where I have full control of lighting, atmosphere, and other conditions.

The software I am primarily using to do all this is The Foundry's Modo.